Sesario’s earliest memories of FLOC are of farmworkers walking out of the fields during the 1968 strike. “It happened so fast,” he remembers, “and we had something like $36 in the organization’s bank account. We did the strike on a farm where the grower was the president of an association representing growers in the area. A local union donated hot dogs and we had mariachis, and we did the 3 day strike right there on the grower’s property.” Even with few resources, Sesario says this first strike sent a powerful message: farmworkers were a force to be reckoned with. “The first strike really made us feel empowered. We were taking people right out of the fields, and it was really powerful.”

Sesario’s roots are in Texas, but he spent many of his early years traveling. Born in Crystal City, Texas, to a family of 10 children, Sesario remembers leaving school early some years to migrate north to work the fields. Sesario’s dad worked for a railroad company in Texas, but was able to make more money working in the fields in the summer. So, he took summers off to follow the “migrant stream”, a path from the South to the North migrants frequently traveled throughout the season to find field work. Sesario and his family first traveled all the way North to Minnesota, planting sugar beets, then moved on to North Dakota to work in the onion fields, and then return to Minnesota to harvest the sugar beets. Then they worked their way South to Oklahoma to pick cotton. “Being a large family, it was hard. We all had to help provide for the family.”

In 1947, Sesario’s family moved to Ohio, where they worked in the cucumber and tomato fields—the same fields that he would later work with FLOC to organize. After graduation from high school in 1958, Sesario joined the Army. He served for 8 years – 6 months as active duty, and then almost 7.5 years in the Reserves. Three of his brothers served in the military as well; one brother did a tour as a machine gunner during the Korean War. “A lot of Mexican-American families have family member who have served in the military,” he says. “It’s common to visit homes and see pictures of family members in their uniforms. They’re very proud of this service.” He says the Army gave him time to think about what he wanted to do with his life, and work toward a college degree.

The work ethic Sesario learned in the fields prepared him well as he entered his 20’s, pursued higher education and entered the job market. Sesario quickly became a “jack of all trades.” He studied psychology and sociology and earned an Associate’s Degree in social work. He studied labor history and various trades. He has worked repairing vending machines and televisions, and he has worked in factories, including a plant that makes pots and pans. He even worked on the instruments that check measurements on jet engines at Continental Aviation for a period of time, and tutored non-English speaking children. If Sesario didn’t know how to do a job, he quickly proved he could learn.

In 1968, he met Baldemar Velasquez, who at the time was just beginning to organize farmworkers in Ohio. Sesario listened as Velasquez spoke at a church gathering, and remembers thinking, “Wow, this guy can talk! He was charismatic, he was believable, and right away he convinced me to get involved.” Sesario and his brother, Ysidro, who was also organizing in the Latino community at that time, started visiting migrant labor camps and talking to farmworkers about FLOC. “Within a short period of time, we had worker meetings and workers were calling for a strike.”

That first strike solidified Sesario’s dedication to FLOC and to organizing, and for the next 10 years, Sesario worked with FLOC on the weekends, evenings, and in between jobs to continue to build a base of support in the fields and in the community. “We used to go house to house and invite people to a meeting on a Sunday, and hold the meeting in a park so people could bring their families. In those early days, we did a lot of politicizing, and we need to do more of that now. People have to hear about injustice again and again, until they get mad about it.”

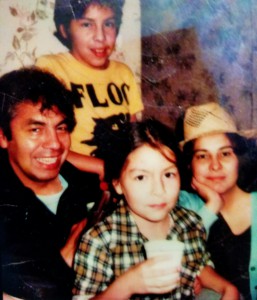

Sesario’s wife, Lucy, and his two children, Sonja and Tony, were also involved in the organizing work. Sesario notes that women played an especially important role in the early years of FLOC’s organizing. “Lucy and I would go out to camps together and talk to people, and sometimes when I would talk to the men they would say things are fine. But when Lucy talked to the women, they would say, ‘We need help getting food stamps, and the bathrooms and showers in the camp are terrible!'” Lucy says she was able to connect on a personal level with the women, and they felt comfortable opening up to her about problems in the fields and in the camps. “The women not only worked in the fields, they also cooked at the camp, cleaned, and then got meals ready for the next day. They knew about all of the problems,” Lucy remembers.

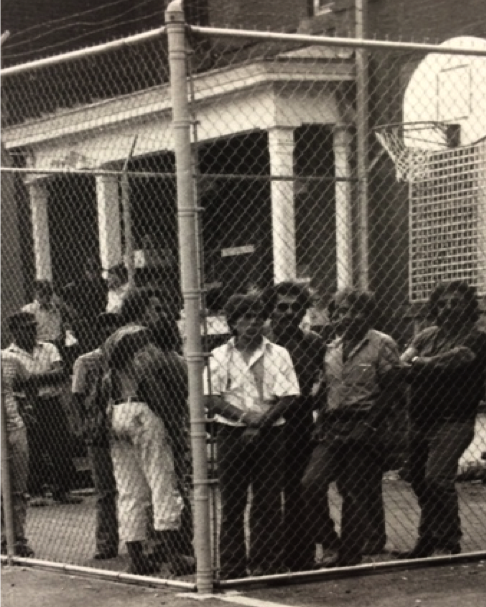

In 1978, after years of slow progress and little noticeable improvement in field conditions, the union launched another massive strike. This time, after years of organizing in various counties around the state, more than 2,000 workers participated in the strike. “We drove in around in a huge caravan, and field by field workers joined the strike,” says Sesario. As the union grew, Sesario dedicated more and more of his time to the work. For a few years he ran the union’s co-op, which served as an organizing base foor the community. “It’s what gave me a lot of gray hairs,” he says. “I was there from 7:00 in the morning until 11:00 at night. I didn’t know anything about running a co-op, we just learned by doing.”

His effectiveness as an organizer came partly from his own work experience, having seen the difference between union and non-union jobs. “There’s a world of difference between union and non-union jobs,” he says. “When I worked for the vending machine company in Toledo, at first I was only making about $75 per week. Eventually I joined the Teamsters, because I saw that the union was fighting for higher wages. Pretty soon my weekly pay went up to over $100. I saw that being in a union was a good thing.”

He was also a proud member of UAW Local 12 during his time with Devilbiss, a manufacturing company in Toledo, OH. After 17 years with that company, he took a non-union manufacturing job making pots and pans. “After working a union job, it was so different. I had to fight management all by myself. Even though I learned how to advocate for myself from FLOC, the hardest part was that there was no union there.”

In 1999 after a broken hand ended his work at the plant, he began working full time for FLOC. He laughs as he remembers his first day in the office. “Some kid handed me some paper and pencils and showed me a computer, but the computer didn’t even work!” For the past 16 years, he has dedicated countless hours to organizing the community through the worker center in the FLOC office, working with immigrant workers to find jobs, navigate a complicated immigration system, translate when needed, and continue organizing workers in the camps.

In 1999 after a broken hand ended his work at the plant, he began working full time for FLOC. He laughs as he remembers his first day in the office. “Some kid handed me some paper and pencils and showed me a computer, but the computer didn’t even work!” For the past 16 years, he has dedicated countless hours to organizing the community through the worker center in the FLOC office, working with immigrant workers to find jobs, navigate a complicated immigration system, translate when needed, and continue organizing workers in the camps.

Sesario has seen many changes in FLOC and in organizing over the years, and through all of the struggles he has only grown more passionate about organizing and expanding union rights. “Now days, you don’t have to fight as hard to get into the labor camps, like we had to before. Sometimes we couldn’t even get into the camps to talk to the workers without getting arrested. And today, more undocumented workers are a part of the fight. It was a lot harder before.”

Next year FLOC will celebrate its 50th anniversary, and Sesario is proud to say that he has been a part of all of the major historic moments in the union’s history. He says FLOC gave him opportunities he will never forget. “I was able to travel all over the world with FLOC — to Mexico, to meet with the leader of a Mexican farmworker union, to Russia, to Czechoslovakia, to Libya, to Cuba. I met Fidel, and his brother took us out to the new farmworker camps in Cuba.”

Next year FLOC will celebrate its 50th anniversary, and Sesario is proud to say that he has been a part of all of the major historic moments in the union’s history. He says FLOC gave him opportunities he will never forget. “I was able to travel all over the world with FLOC — to Mexico, to meet with the leader of a Mexican farmworker union, to Russia, to Czechoslovakia, to Libya, to Cuba. I met Fidel, and his brother took us out to the new farmworker camps in Cuba.”

Today, Sesario is 78 years old, but you’d never know it by how quickly he can fill a bus of community members to head to a union event.

Help us honor Sesario and his nearly 50 years of work with FLOC, by supporting the “Voces: Somos FLOC” campaign.

Will you donate $25, $50, $75, or whatever you’re able to support member organizing? You can easily donate online here, or send a check to 1221 Broadway St. Toledo, OH 43609. Thank you for your generous support!